Why return to the Moon?

The exploration of Earth's natural satellite has a long history. As early as 2 January 1959, the Soviet space probe Lunik 1 was launched to the Moon. Since then, many space probes in the Soviet Luna programme as well as in the Ranger and Surveyor programmes of the USA have gone there. Then came Apollo and with it the landing of the first and last 12 astronauts on the lunar surface. But after the last two astronauts, Eugene A. Cernan and Harrison H. Schmitt, left the Moon in December 1972, the Russian rover Lunochod 2 came to a standstill after an incredible 42 kilometres in 1973, and Luna 24, the last lunar probe at the time, brought 170 grams of rock back to Earth in 1976, interest in our satellite was left in the moondust, so to speak. In 2009, the fascination for the Moon was reawakened internationally when Chandrayaan-1 (India) discovered water – or more precisely hydroxyl ions in minerals – on the lunar surface. When the US Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which was launched on 18 June 2009, confirmed the Indian observation a short time later, new interest was finally sparked. Thanks to German support, LRO provided the basis for a revised coordinate system of the Moon, precise topographic maps of the surface, the search for suitable landing sites for future missions, the search for volatile elements – particularly water ice in the craters of the polar regions, data on the frequency of meteorite impacts on the surface and information on the history of the Moon. In addition, LRO was instrumental in giving substance to the Moon euphoria, because in 2017 a US study using LRO data was able to show that the lunar mantle could probably contain similar concentrations of water compared to the Earth's mantle. Suddenly, our Earth companion became interesting again. Nevertheless, we know more about Mars than about the Moon, which is much closer to us. More rock samples from other areas are needed to better understand its history – and thus also the history of Earth and the Solar System. At the same time, the Moon has also become interesting for space companies. Because if humanity wants to get to Mars, it cannot bypass the Moon. The Moon is becoming a stepping stone for the journey to the Red Planet. This requires infrastructure to be built on the surface and in orbit. This also paves the way for certain services. That is why, 50 years after the Apollo 17 mission, the Moon remains an important target and continues to fascinate humankind.

German technology takes the USA to the Moon

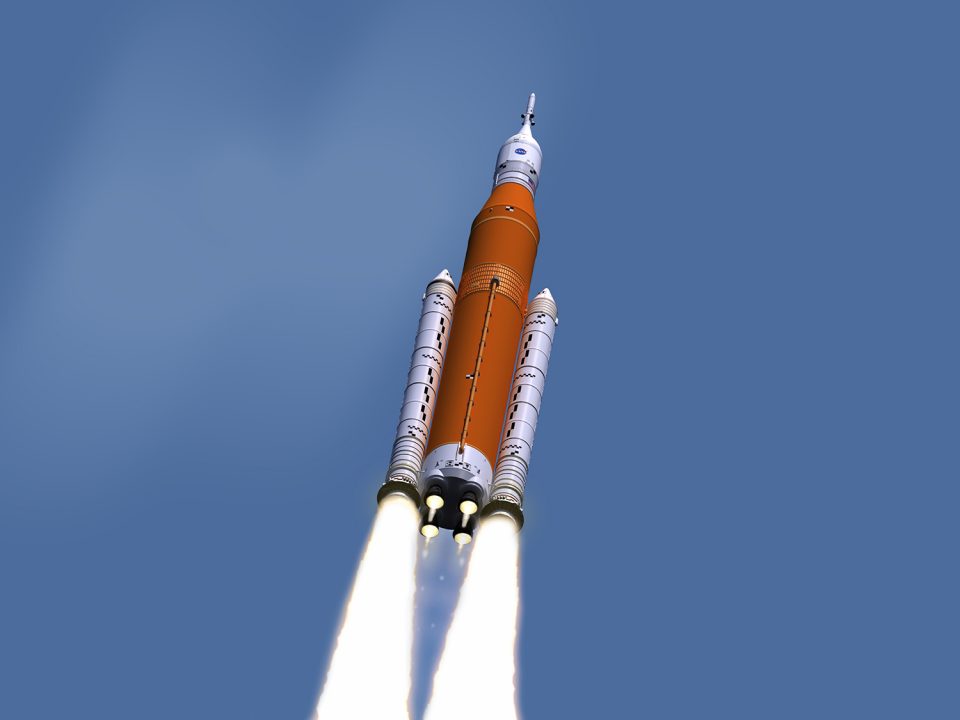

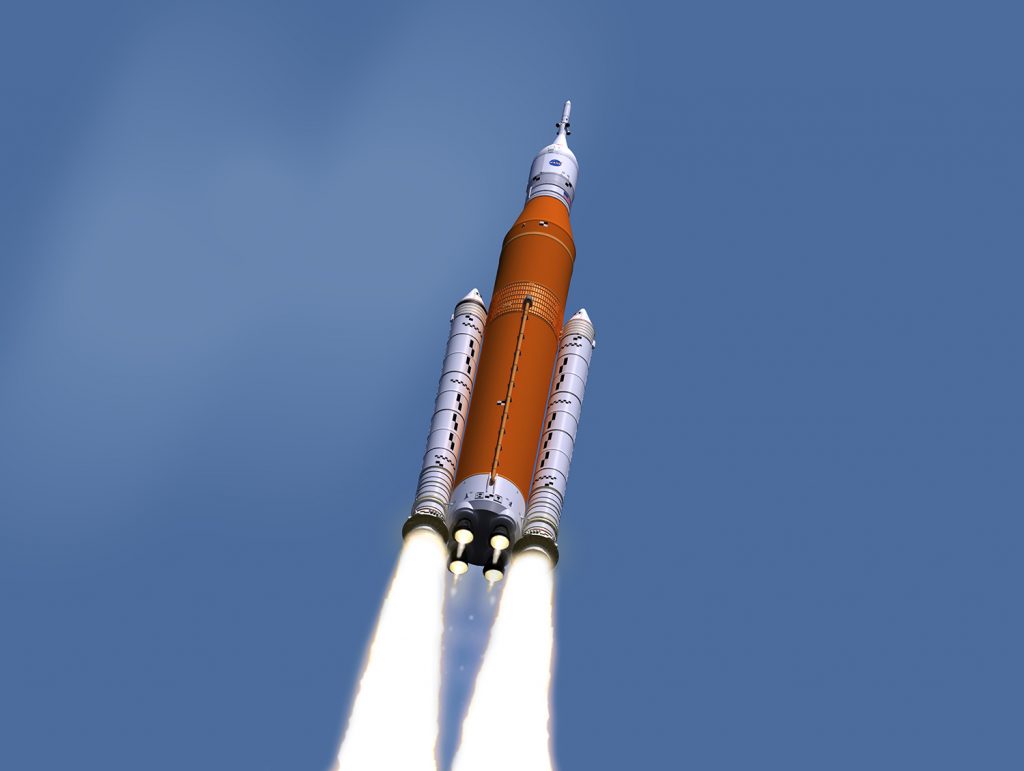

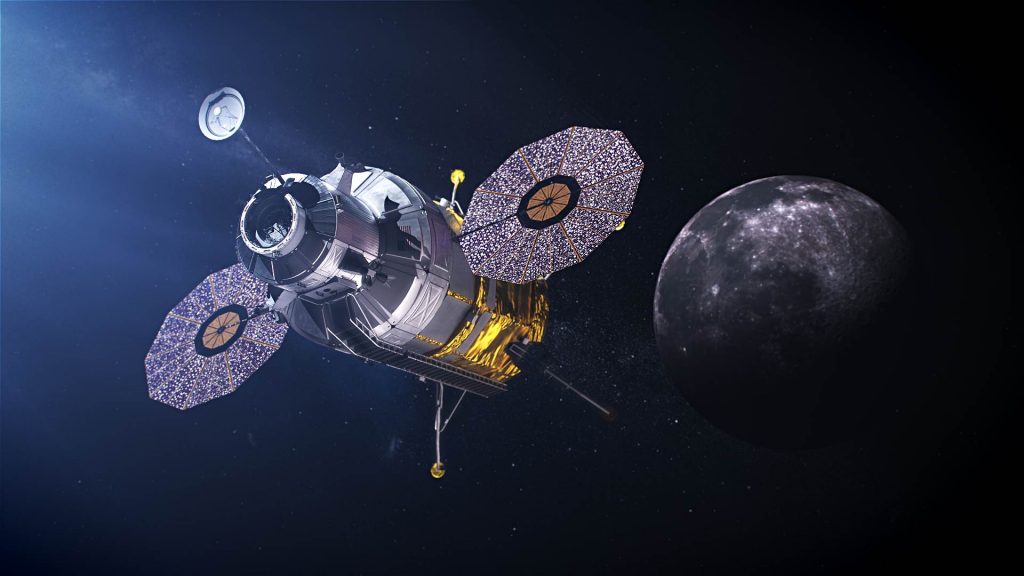

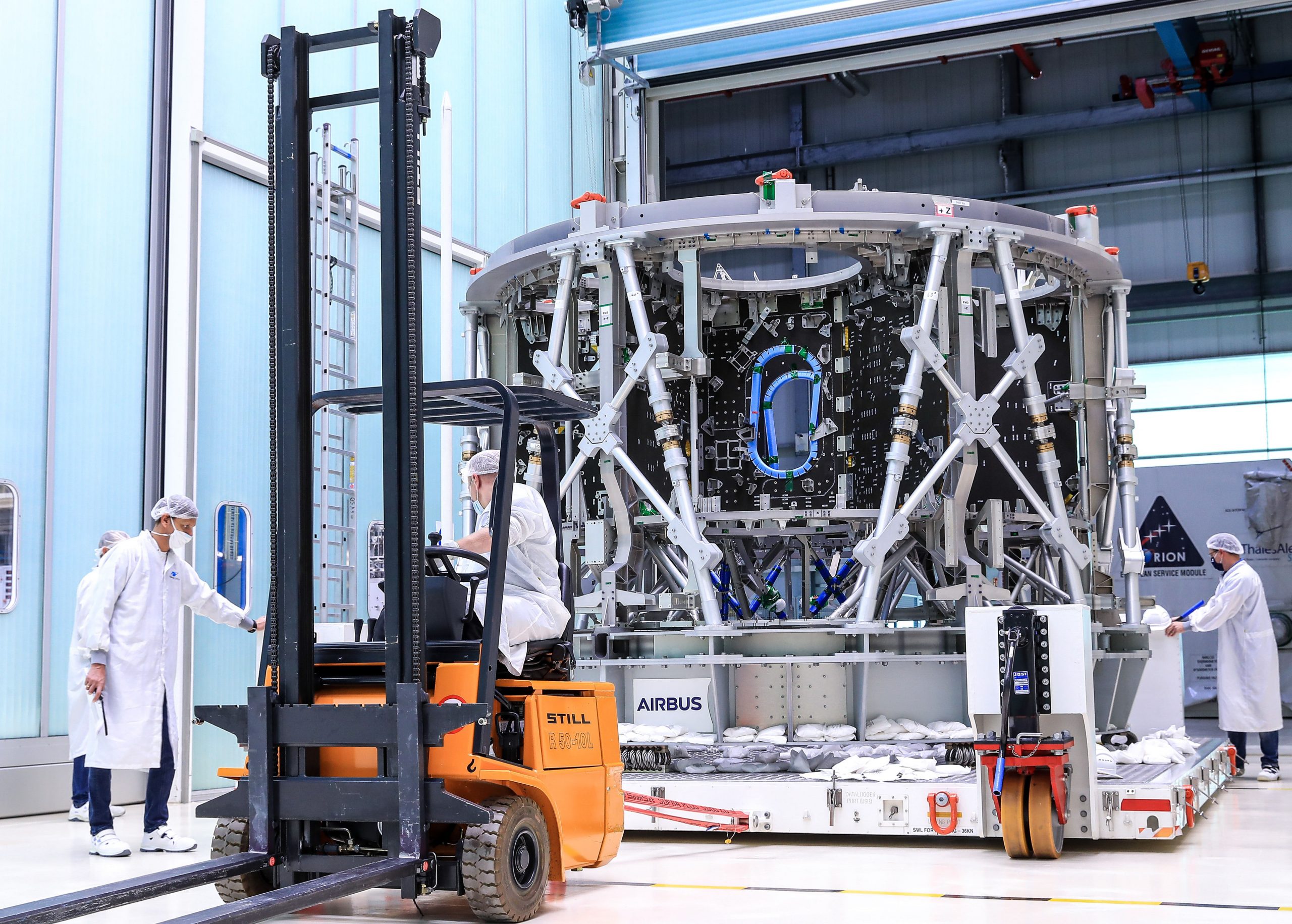

When on 16 November 2022 the Artemis I mission lifted off from Launchpad 39B at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the green light was given for the astronautical return to the Moon. After several postponements, the new SLS Block 1 launch vehicle took off with the first Orion spacecraft in the direction of Earth’s natural satellite and splashed down safely back in the Pacific Ocean at 18:40 CET on 11 December 2022. But the return to the Moon is not strictly a US undertaking: when the first, initially uncrewed Orion spacecraft set off on its orbit around the Moon in preparation for future crewed missions, it was propelled by German technology and set on course towards Earth's natural satellite. Future Orion space capsules will continue to be brought to their destination by this propulsion and supply system – the European Service Module (ESM). NASA has commissioned six of these ESMs from the European Space Agency (ESA) as part of its Artemis programme, and Airbus in Bremen is primarily responsible for their construction. That is why the first module, ESM-1 Bremen, is named after the Hanseatic city. Six more are to follow.

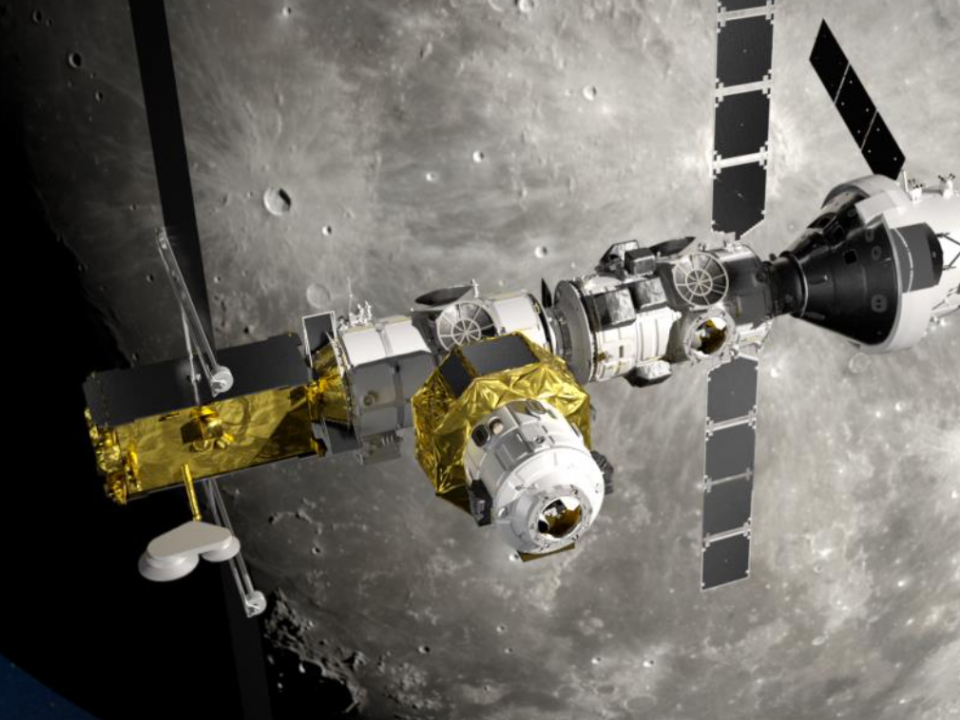

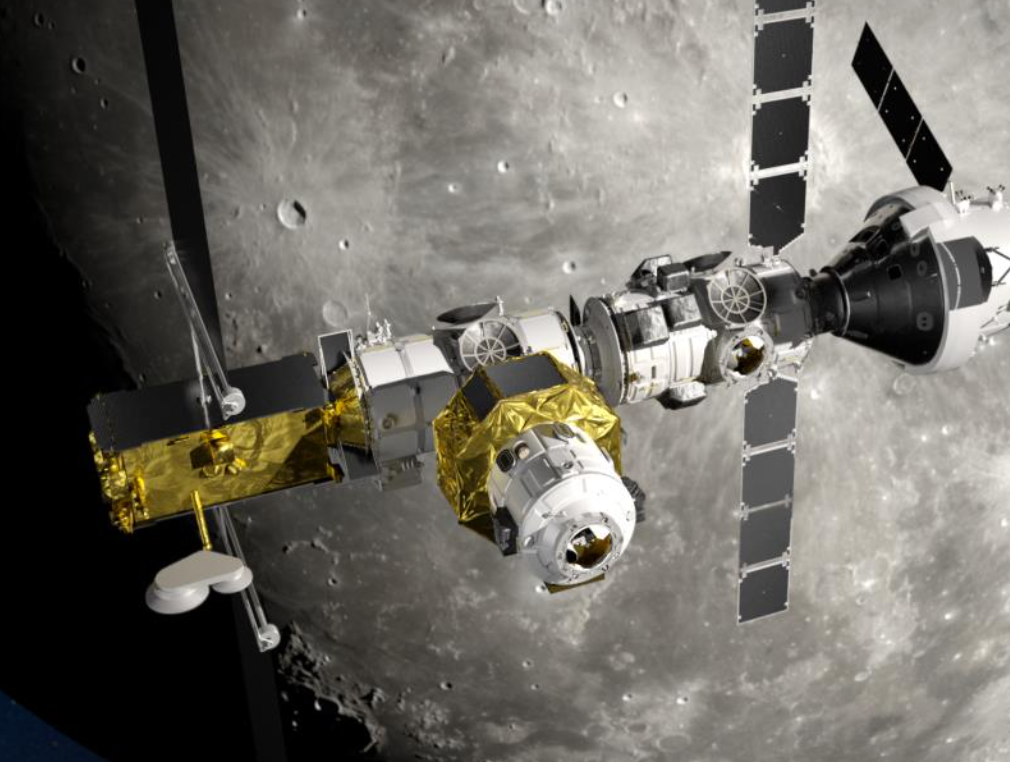

The ESMs are the heart of all Orion spacecraft and sit below the crew capsule. In future, their main propulsion unit will again take astronauts to the Moon – including, for the first time, three Europeans to the planned international lunar space station Lunar Gateway – and supply the power for their flight via four solar panels. It will also regulate the climate and temperature in the spacecraft and store fuel, oxygen and water supplies for the crew. The Orion spacecraft, and with it the ESM, are regarded as a key milestone for future astronautical missions to the Moon, but also to Mars and beyond. ESM-2, which will carry Artemis astronauts into lunar orbit for the first time, has already been delivered. ESM-3, which is planned for the first Artemis lunar landing mission, is currently under construction.

Dr Walther Pelzer

DLR Executive Board Member and Director General of the German Space Agency at DLRArtemis in the future

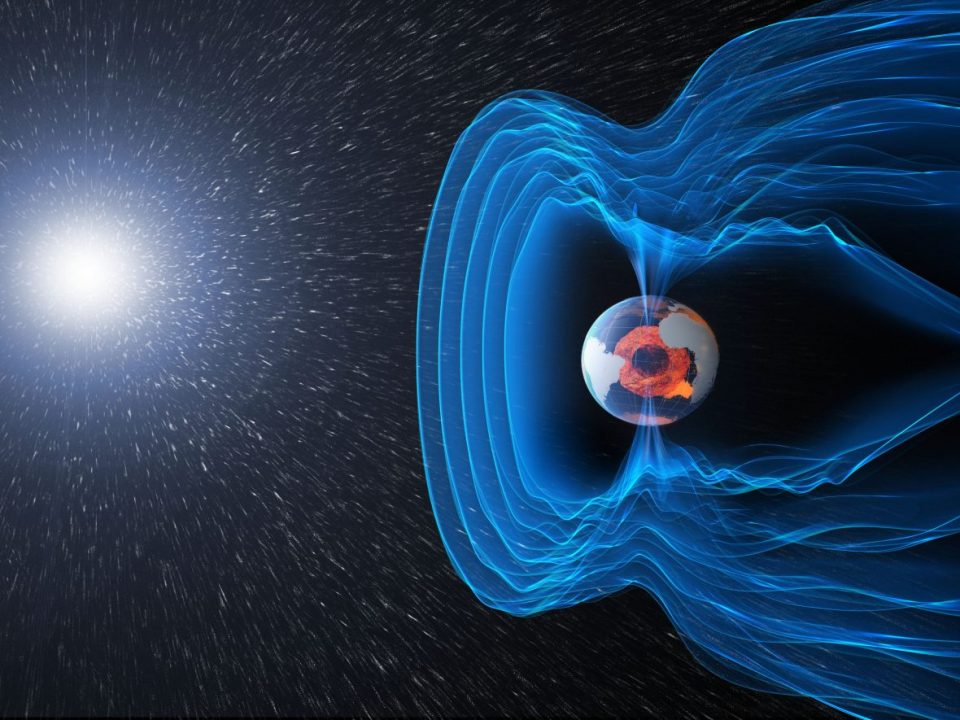

The Artemis missions are uniquely focused on expanding our knowledge of our perpetual cosmic companion and establishing a long-term human presence on and around the Moon. In doing so, NASA is focusing on the flight to the Moon, the landing sites around the South Pole, the establishment of the Gateway space station in lunar orbit, and the extension of astronaut exploration time on the lunar surface. To best meet the requirements of the missions, NASA is involving international partners and increasingly industry in the development of technology for Artemis. As part of the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, for example, NASA is working with several US companies to bring science and technology to the lunar surface. In this way, NASA can share its knowledge and maintain oversight of safety while the industry partners develop, test and refine their designs. But NASA is already thinking ahead: once humans have 'made themselves at home' on the lunar surface, NASA will launch its Lunar Surface Innovation Initiative. Here, technologies will be developed and demonstrated to harness the Moon's resources to produce water, fuel and other supplies on site, as well as to investigate capabilities for excavating and building structures on the Moon. This is because the farther humans venture into deep space, the more important it will become to manufacture products from local materials, known as in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU).